Books

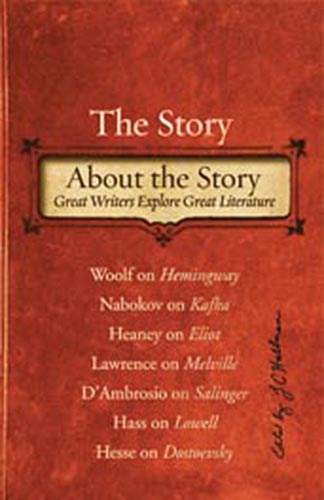

Partial Introduction to Volume 2

It may be that the experience of teaching writing and literature offers up an even better explanation for the state of books in the world than the teaching of the craft of creative writing. By the time someone has taken a creative writing class (and decided to take it at least a little bit seriously) they’ve sort of already made it over the hump, and you don’t have to worry about whether that person is ever going to give stories or poems a chance—they already have. The teaching of writing and literature, however—and by this I mean entry level composition courses, entry level English courses, the kinds of classes often handed off to MFA students—is more like the front line of the war: you see students fresh out of high school, and when it comes to the state of books in the world, the typical teacher of this kind of course is probably more like a chicken sexer than anything else. Sure, you give them grades at the end of the semester, but probably by day three or four students have lifted their literary leg, as it were, and a good teacher will have mentally separated those who will get it from those who won’t and dropped them in the appropriate bucket: won’t get it, won’t get it, won’t get it, might get it, won’t get it, won’t get it, won’t get, gets it, won’t get it, won’t get it, won’t get it, and so on.

Of course the problem is that all of these won’t-get-its are people who should really be buying books eventually—or at least they would in a better world than ours. It’s common these days to scoff at any vision like this, any vision that sees literature as anything other than an activity for a select elite. Much better, this theory appears to suggest, is some variation on the perpetual shock that was accidentally delivered to the not-apocryphal dog that forgot how to learn to even attempt to escape its punishment. Modern literature is just like that—modern literature relishes its learned hopelessness, revels in a kind of group depression in exactly the same way it celebrates the clinical tax so often levied on its practitioners, wears its angst like a studded fetish collar connected by a short lead to who knows what mysterious and demanding master. The result is even worse than what’s become of opera—at least there are people who can’t sing a lick who still go to the opera.

I, for one, don’t think writers should just sit around and admire one another’s ennui. There is something to be done, there is a solution. And the solution has to do with how we write about literature—the craft of criticism.